Site Description

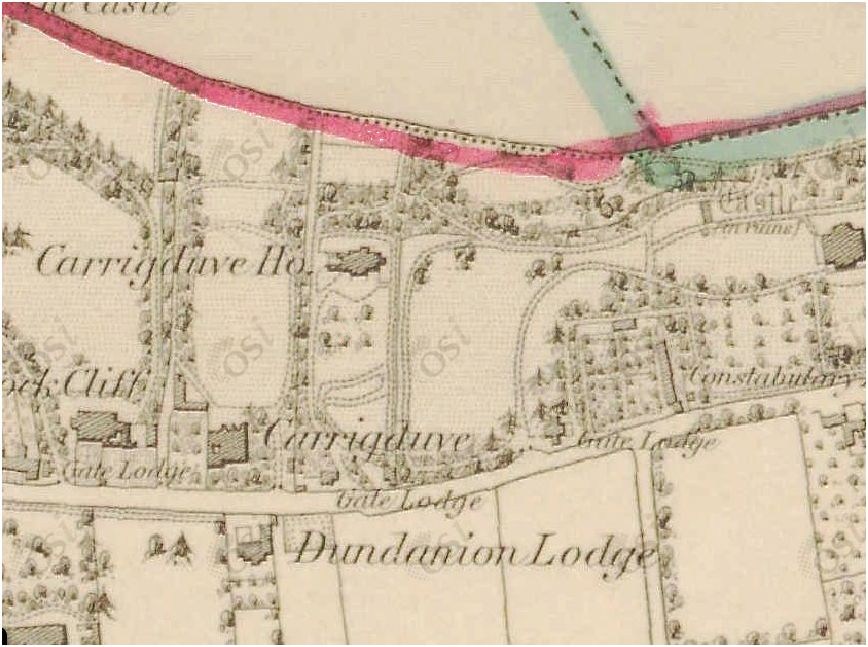

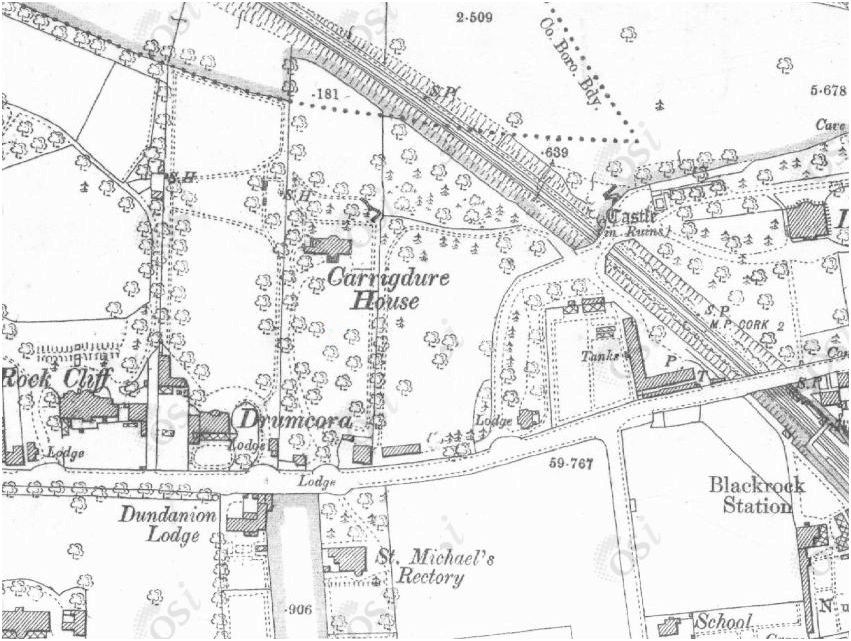

The site of Dundanion Court was once part of one of Blackrock’s many historic houses from the 18th and 19th centuries. Blackrock, and the Mahon Peninsula are described in Lewis’ Topographical Dictionary of 1837 as ‘fertile’ and ‘beautifully situated’. Richard Henchion’s ‘East to Mahon’ gives a story of the history of the Mahon Peninsula, including the townland of Dundanion, in which the development is situated.

The site is situated between Carrigduve House and Dundanion House. It was annexed from Dundanion House by the construction of the Blackrock and Passage Railway line, and a neo-gothic Cork limestone bridge was constructed to maintain the route from the entrance to the house across the railway. Dundanion House is best known as the home of the Deane Family and the noted Irish Architect Sir Thomas Deane who bought and renovated the house in the 19th century.

The site contained many mature trees which were incorporated into the development. The significant line of trees currently on the west side of the site can be seen on the 25inch historic map.

Historical & Architectural Context

The site was leased for development by Daniel Hegarty (Housing) Ltd to a design by architect Neil Hegarty who worked in that family business. Neil began the study of architecture in1956 as a member of the first class of the newly established School of Architecture based in the Cork School of Art, and after Intermediate in 3rd year, at Oxford, England where he qualified in 1962.

While studying he visited the Brussels World Fair in 1958, and saw buildings of Pier Luigi Nervi in Rome when there as a member of the Irish Olympic team. At Oxford was able to watch the construction of St Catherine’s College, by Arne Jacobson, (now a grade 1 listed building) visiting the site regularly and learning construction techniques. The year following graduation Neil travelled to the Unites States with his new wife Angela.

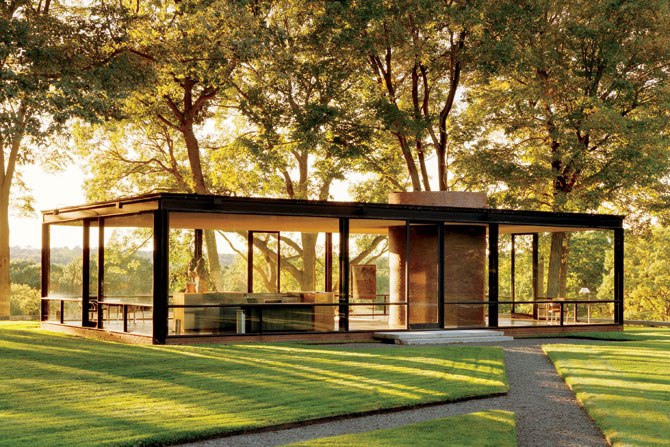

He was given a list of architecture to visit on the east coast by his friend Gerald McCarthy who was then working at Eero Saarinen and Associates the U.S. Neil and Angela visited Quebec, Montreal, Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Washington, Chicago, Detroit & Philadelphia. While in The U.S. Neil studied the work, and visited the buildings of Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Louis Kahn, Frank Lloyd Right, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, Paul Rudolph and Minoru Yamasaki. He spent an afternoon with Philip Johnson in his own residence the ‘Glass House’ at New Canaan Connecticut, while he was living there, and also met John M. Johansen, architect of the American embassy in Dublin, in his residence close by to the Glass House.

Dundanion Court was designed in the year following Neil and Angela’s visit to America. Neil was strongly influenced by Lafayette Park in Detroit designed by Mies van der Rohe with Hilberseimer as Landscaper, (now on the National Register of Historic Places) and considered to be one of the most continuously successful districts in Detroit. This design success is considered to be attributable to the collaborative approach employed from planning stage to the design of the buildings and the integration of the landscape. In referring to Lafayette Park, Mies Van der Rohe lamented the loss of understanding of order that he said had been understood in the past.

Lafayette Park Detroit

Neil studied and was influenced by highly considerate integrated housing and landscape projects carried out in northern Europe and the U.S. from the 1930’s onwards but particularly in the 1950s and early 60’s, including work of the internationally recognised Danish Architect Arne Jacobsen.

Neil Hegarty went on to work as a senior executive architect in Cork County Council and as City Architect in Cork Corporation / City Council. His studies and experiences prior to and in the design and construction of Dundanion Court went on to change Cork County and City policies on housing, regeneration and development.

Living Environment and the Lease

The approach that Neil identified with was similar to that of Span Developments, working in the UK at the same time. Span built over 2000 homes in the south of England combining modernism, and attention to detail, and placing it in harmony with the surrounding landscape. Span consisted of an architect, landscape designer and developer.

Span’s architect Eric Lyons was scathing about the modern movement’s poor treatment of landscape and, like Neil he had a strong interest in community and engaging people with carefully planted external space. To safeguard the visual unity of the building exteriors and the open spaces, Span was determined to solve the problem of how the common parts of such schemes could be successfully maintained and managed. The resulting sense of community, engendered by participation in a residents’ society, and the care of communal spaces by an associated scheme of management, has been considered by some to be the greatest achievement of Span, its benefits being both aesthetic and social.

Today the housing developments carried out by Span retain their original intention and are highly sought after by a new generation of people who have an interest in their aesthetic and functioning community structure. This has been recognised by local authority conservation officers and English Heritage. The 1960’s and 70’s aesthetic of the Span interiors often feature in lifestyle and interior magazines.

The following extract from the book, ‘Eric Lyons & Span’, is as valid for Dundanion Court as it is for Span developments:

“ the core ingredients are simple, even modest: an invisible boundary between landscape and building design; the provision of attractive shared spaces and architectural design that allows the homeowner to be part of the shared space or be separate from it.” (Ed. Barbara Simms, Eric Lyons & Span, RIBA Publishing 2006).

In the development of Dundanion Court Neil worked with solicitor Michael O’Driscoll in drawing up property leases that were influenced by the Span approach. Michael was both personally and professionally interested in new ways of structuring property leases and shared an interest in new approaches to development. The nature of the lease is to combine the safeguarding of the visual amenity with an equitable communal approach, more in line with a modern apartment development than a traditional housing estate. The lease on each property requires the owner to pay one thirty-sixth part of the running and repair of the common facilities, to maintain the premises in good order, not to change its appearance, or to erect anything that would change the visual appearance.

The Development

Dundanion was designed to be high quality housing for a new generation of professional and business people, adopting new technologies and approaches, and being fitted out with natural and often expensive materials. A high quality hardwood was chosen for internal joinery; cedar was used for external cladding and for internal ceilings; white Carrara marble slabs were inset into kitchen worktops and a significantly large polished dark Irish limestone mantle shelf was installed. Aluminium horizontal sliding windows were imported from the U.S. and polished cast aluminium handles were used on doors with polished cast aluminium numbered letter plates. Many things were the best of their kind and also the first of their kind in the country. Options were given to residents in the fit-out, and sliding wardrobes, kitchens and built in furniture were constructed by the firm’s joinery shops.

The materials of brickwork, timber, steel and stone were used in a clear and simple manner. The distillation of the design ideas to create the simplicity represented the combination and balance of a complex set of ideas relating to architecture, materials and space. As at Lafayette Park, the design employs an intensive use of space, purposefully balancing economies of design, construction and materials but with the extravagances of solid materials of hardwood and stone.

There are four rooms and two bathrooms on the first floor with one of the bathrooms off the dedicated master bedroom. The ground floor is open plan between sitting and dining rooms, with a separate kitchen and entrance hall. The main entrance hall opens to the courtyard, while the garden door to the kitchen opens onto a walled private garden. Internally full height glass screens are used between the kitchen and sitting / dining areas and as a screen around the main stair. These have the effect of maximising the feeling of space within an economic plan and separating sound between the floors.

The interface between public and private space was carefully considered. The entrance and garden doors are recessed to add detail and rhythm to the terraced blocks and provide shelter. The courtyard door recesses provide progression between the shared courtyard and the interior. It was envisioned that people might sit on their courtyard door step in good weather. Half doors were installed to the garden entrance recess in the manner of an Irish farmhouse.

Cars are parked on shared vehicle/pedestrian surfaces, and blind right angle corners are maintained to slow vehicles. Various devices are employed to encourage people to meet and maintain privacy when desired. They include narrow footpaths in courtyards, narrow entrances to courtyards, relatively low walls to gardens and communal car parking. Public lighting was low-key and architectural.

There were many technological aspects of Dundanion Court that were new to Ireland, and are now more commonplace; some used for the first time here. The national electricity board were brought on board the new ideas for the development and offered a site for a substation that is integrated into the scheme. They agreed to move the street lighting and power cables to the far side of the Blackrock Road so that they would not interfere with the formal elevation of the development to the public road. A new approach for Ireland was the burying of all electrical cables, telephone wires and TV ariel wires to maintain clean elevations and landscape. A TV hut was constructed on the north east corner of the site that would contain a single TV ariel for the whole estate as well as electrical supply for lighting. Electrical underfloor storage heating was used throughout on the ground floor with no radiators to impede the spaces. Drainage pipes were brought down internally and exposed as part of the architectural expression of the building and small diameter exposed soil vent pipes were used. Fairfaced concrete elements were carefully cast on site using ‘Formica’ in a reusable mould former for the concrete. Floor joists were supported on fabricated steel joist hangers. Ply sheeting with hardwood veneer was used on flush doors and walls upstairs. Particle board was used where it would not be seen in combination with hardwood veneers and edgings. Particle board was used to form the first floor and roof deck. Steel beams on fair-faced concrete padstones split the first floor and roof joist spans as required, and vertical damp course breaks in the brickwork prevented moisture ingress and condensation around external doors and windows. Glass insulation was installed in the roof and timber external walls. White net curtains, so fashionable in architecture at the time, were provided by the developer before occupation.

The south courtyard was constructed first and occupied, with the north courtyard following. The list of original residents is one of professional and business people, as was the intended market, however towards the end, sales were slower and prices were reduced. There are some minor indications in the finished development of the pressure that the developer was under to finish out while constraining spending. Neil occupied Number 1 with his family for eight years and moved to the family house where he grew up when his father downsized.

When asked about the construction process, Neil noted the large amount of time and workforce that had to go into the installation of the stone mantle shelves, as well as the high tolerances required in the installation of timber windows and internal joinery. On the first floor the finished cedar ceilings were installed before the partitions and doorframes.

When designing the courtyards the existing 19th century specimen trees of Dundanion House were maintained and used to deliberately create external space and maturity within the landscape. This added great drama and a layered sense of continuity to the external space. The layout of roads and blocks were designed from the outset to maintain the mature trees and new trees were planted on completion.

Following Construction

In 1975 it was announced that the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland awarded the Medal for Housing for the period 1968-1970 to Neil Hegarty for Dundanion Court, with a significant amount of media coverage. The delayed period was to allow buildings to be assessed on their performance following occupation, as well as the constructed design.

A notable storm swept the country on the night of 11/12 January 1974 causing extensive damage throughout the country. At Dundanion court the light timber fences separating private gardens were broken and were subsequently replaced with masonry walls.

Since construction barbeques, children’s birthday parties and other low key social events have taken place intermittently in the common courtyards and children come from the surrounding areas with their parents on Halloween night to go door to door in the contained car free environment.

In 2001 Dundanion Court featured in an issue of Building Material published by the Architectural Association of Ireland and more recently the newly formed Cork Centre for Architectural Education and Limerick University Architectural Dept. have visited to study and survey the development from an historic perspective.

Today a new generation is attracted to Dundanion for the same reasons as at Lafayette Park, Span Developments, Eichler houses and other such rare developments. In the past two and more decades there has been a renaissance in interest in modern design, and even retrospective modernism, as well as the desire to live in places with identity, rather than today’s speculatively built housing, often poorly integrated into their environments.